| COLONIALA Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: The First Century |

|

CHAPTER 6:

A Brief Survey of Anglo-Indian Interactions in Virginia during the Seventeenth Century

Edward Ragan

The first century of Anglo-Indian interaction in Virginia can be understood as a prolonged period of adjustment for both the Native inhabitants and the European settlers. The dominant histories of Jamestown have long told of the challenges faced by the English in the permanent settlement of their "New World." Those histories have frequently overlooked the "New World" realities faced by Tidewater Algonquian communities. Structurally, the seventeenth century marked a dramatic declension in, but not a disappearance of, Native communities as they adjusted to the English presence. Decimated by disease, outnumbered Algonquian warriors were defeated militarily. Once beaten, tribal communities were subjugated politically under the English crown and categorized racially under Virginia law. The focus of this essay is that period of adjustment—physical and social—to English settlement.

Physical Adjustments

Whatever its source, death was the inescapable certainty of the Anglo-Indian encounter in the Chesapeake Tidewater. Old World diseases preyed upon Algonquian communities for at least the first century of English settlement. Infection, along with warfare, murder, and dispossession at the hands of English settlers caused Native populations to decline by about ninety percent across the seventeenth century. Sickness traveled to Native communities with the first English traders to begin the assault, and virgin soil epidemics, such as smallpox, influenza, measles, and tuberculosis, erased entire communities.1 These contagions tended to hit hardest those between the ages of fifteen and forty: providers, protectors, and perpetuators of their communities. For the very young, these diseases were almost always lethal, if not from infection then from neglect by parents too ill to care for their own. To make matters worse, native treatments, while effective for pre-contact ailments, tended to make virgin soil epidemics more lethal. European disease did not respond to the Algonquian's customary sweatlodge and cold bath treatment, and Natives had no concept of quarantine for the sick.2 It would take an entire century for Indians to incorporate the "Old World" and its dangers and almost as long for Englishmen to acclimate to the "New."

1Thoms Hariot, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (London, 1590; reprint, New York: Dover, 1972), 28.

2Alfred Crosby, "Virgin Soil Epidemics as a Factor in the Aboriginal Depopulation in America," William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 33 (April 1976): 292, 294-95, 296-97; James Merrell, "The Indians New World: The Catawba Experience," William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 41 (October 1984): 542-46.

Newcomers to Virginia, required a "seasoning" to their new environment, and still, it was fatal for most, "not one of five escaped the first year."3 They fell victim to a host of deadly prey: "cruell diseases, ... Swellings, Flixes, Burning fevers, ... Warres [with Indians], and some departed suddenly, but for the most part they died of meere famine."4 Starvation, disease, and warfare threatened the immigrant daily. Unseasoned immigrants who arrived from England in the summer, when it was "very unhealthy" died "during these months, like cats and dogs, whence they call it the sickly season."5 One way to improve the immigrants' survival was to import them during the winter when Indian corn had been harvested and was more plentiful for trade, and the cooler climate could ease non-Natives' adjustment to Virginia.

3William W. Hening, ed. The Statutes at Large, Being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature, 13 vols. (Richmond: Samuel Pleasants, Jr., 1809-23), 2:515.

4Alexander Brown, Genesis of the United States (Boston: Russell and Russell, 1890), 1:167; Carl Bridenbaugh, Jamestown 1544-1699 (New York: Oxford, 1980), 45.

5David Pietersen de Vries, New-York Historical Society, Collections, 2d ser., 3:7, 75, 77, quoted in Bridenbaugh, Jamestown, 46-47.

The First Expansion of English Settlement and the First Anglo-Powhatan War

Another solution was to get as many people out of Jamestown as possible. In 1609, John Smith was still the president of the colony, and he devised a plan to extend English settlement from the falls of the James River to its mouth on the Chesapeake Bay. This was a practical solution to feed his starving colonists. The nearby Native communities at Paspahegh and at Kecoughtan refused to sell any more corn to the starving English settlers. By moving the bulk of the population out of Jamestown, Smith hoped to take advantage of Indians further away, the Nansemond who lived downriver from Jamestown and the Powhatan (the ancestral village of the paramount chief with the same name) at the falls. For Smith, this decision was also a military opportunity to gain control of the James River valley.6

6For Smith's attempt to limit the disasterous effects of disease at Jamestown, see Carville Earle, "Environment, Mortality, and Disease in Early Virginia," in Thad W, Tate and David L. Ammerman, eds., The Chesapeake in the Seventeenth Century: Essays on Anglo-American Society, 96-125 (Chapel Hill: University of North Caroline Press, 1979), 107-8. For Smith's "politico-military motives," see Helen C. Rountree, Pocahontas's People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia through Four Centuries (Norman: University of Pklahoma Press, 1990), 52&n.156.

The English sought to establish new settlements along the James River even though they had not treated the Nansemond or the Powhatan any better than they had the Kecoughtan or the Paspahegh. At Nansemond, fighting broke out when Captain John Martin and his men tried to occupy by force an island where the Nansemond had a village. After repeated attacks upon Martin's men by Nansemond warriors, the English abandoned the island and fled to Kecoughtan. Later, when Martin returned to the island to search for survivors, he found the corpses of several of his men, their mouths stuffed with bread. A clear sign of the Nansemond's contempt for Englishman who asked for too much and gave too little in return.7

7Ibid., 51-52.

At the falls of the James, the English fared little better. There, Francis West and John Smith tried to make the Indians there pay a tribute to the English in exchange for protection. "To defend him [Powhatan] against the Monacans," West insisted that the paramount chief Powhatan sell to the English the Powhatan tribal "fort and houses and all that countrie for a proportion of copper." In exchange, Powhatan's people would become tributaries of the English crown with the following conditions: "that all stealing offenders should bee sent him [to West], there to receive their punishment: that every house as a custome should pay him [West] a bushell of corne for an inch square of copper, and a proportion of Pocones as a yearly tribute to King James, for their protection as a dutie."8 Powhatan rejected this bold offer by the English, and his warriors continued to raid the English settlement. By late fall, West gave up and returned to Jamestown.9

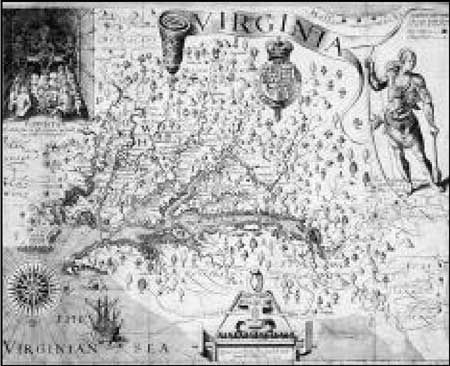

8John John Smith, A Map of Virginia , in The Complete Works of Captain John Smith (1580-1631), vol. 1, ed. Philip Barbour, 119-289 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 270.

9Rountree, Pocahontas's People, 52.

By the winter of 1609/10, the English had been at Jamestown for two-and-a-half years, and still they starved. They had yet to grow crops to feed themselves, relying instead on Indians' corn. There were plenty of deer and turkey in the forests, but they did not hunt them, partially due to the Powhatan siege of James fort. Instead, they scavenged the woods for roots, nuts and berries, and they ate all manner of living animals in the fort — horses, dogs, cats, rats, mice, and snakes.10 Some even resorted to cannibalism. One man chopped up and salted down his wife, and in another case, some settlers exhumed a dead Indian to eat of his corpse.11 In May 1610, at the end of the "starving time," the new interim governor, Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Gates, sailed up the James River to find "three score persons [at Jamestown] therein, and those scarce able to goe [it] alone, of welnigh six hundred, not full ten months before."12

10Smith, Map of Virginia, 263-64.

11George Percy, "A Trewe Relacyon," Tyler's Quarterly 3 (1912), 266-69; Edmund Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom (New York: W.W. Norton, 1975), 72-73; Rountree, Pocahontas's People, 53, & n.170; Earle, "Environment," 110.

12Ralph Hamor, A True Discourse of the Present State of Virginia (London, 1615; facsimile reprint, 1957), 16; Bridenbaugh, Jamestown, 45; William Strachey, "A True Reportory of the Wracke and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates, Knight," in Samuel Purchas, Hakluytus Postumus or Purchas His Pilgrims, [1625], 20 vols. (New York, 1905-7), 19:69; Samuel Purchas, Hakluytus Postumus or Purchas His Pilgrims, [1613] (London, 1613), 632-33.

Gates arrived with instructions to reform the colony, but when he saw its miserable state, he decided instead to abandon Jamestown. He could hardly contain the relieved settlers whom he had to restrain from burning down the fort upon their departure. It was a good thing, too. On their second day under sail, Gates's four pinnaces encountered an English relief convoy loaded with supplies, 300 soldiers, and a new governor, Thomas West, Lord de la Warr. Gates' rag-tag convoy reversed its course and returned to Jamestown. Together, Gates and de la Warr set about to reform the colony and defeat the Indians who constantly harassed the settlers along the James River.13

13Percy, "Trewe Relation," 269; Richard Morton, Colonial Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1960), 26-27; Michael Leroy Oberg, Dominion and Civility: English Imperialism & Native America, 1585-1685 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999), 60-61; Rountree, Pocahontas's People, 54.

Gates's reforms also included a shift in Indian policy.14 The Virginia Company instructed Gates to convert the Algonquians of Tsenacomoco (Powhatan's territory) to tributaries of the English crown. This process involved English sovereignty in the land, the education of Indian children as a means to break the "superstitious" influence of Native priests, and conversion to the English mercantile economy.15 The first component of this plan involved gaining title to Indian land; the remainder were cultural objectives that sought to remake the Powhatans socially and economically.

14Wesley Craven, "Indian Policy in Early Virginia," William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 1 (January 1944): 65-82. For Sir Thomas Gates's instructions (1609) on reducing Indians to tributary status, see Susan M. Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 4 vols. (Washington D.C.: Library of Congress, 1906-35), 3:12-24.

15Helen Rountree, "The Powhatans and the English: A Case of Multiple Conflicting Agendas," in Powhatan Foreign Relations, 1500-1722, ed., Helen Rountree (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993), 188.

In reality, the plan was ambitious and the settlers at Jamestown, who struggled for survival themselves, could do little to entice Indians to join them. In the "necessity" that "Civil peace" could not be restored through conversion, the Virginia Company pronounced to Gates that it was "not crueltie nor [a] breach of Charity to deale more sharpely with them and to p[ro]ceede even to dache with these murtherers of Soules and sacrificers of gods images to the Divill."16 Throughout, the English failed to realize that Indians who were dispossessed of their land would be militant against Christianity, English social customs, and English presence in Tsenacomoco.17 These conflicting goals are apparent in English attitudes about how the Indians ought to be treated as humans and converts to English civilization. The Virginia Company gave the Virginia executive full "discrecion" as to which option he would choose to convert Indians.18

16Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:14-15.

17Rountree, Pocahontas's People, 54, 68-69.

18Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:14-15.

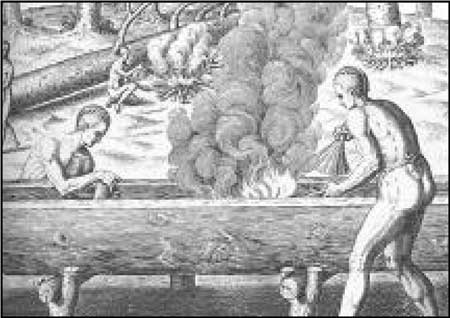

Late in summer of 1610, as the corn that would feed the Englishmen that fall ripened in the fields of Kecoughtan, Paspahegh, and Chickahominy, Gates and de la Warr made their decision. They ordered attacks on these towns to encourage Powhatan's submission to the English crown and church.19 In August, Gates sailed down the James River to Kecoughtan where he ordered his musician "to play and dawnse thereby to Allure the Indyans to come unto him." When the Kecoughtan heard the music and came down to the river's edge, Gates's men "fell in upon them put fyve to the sworde wownded many others some of them being fownde in the woods wth Sutche extreordinary Lardge and mortall wownds that itt seamed strange they Cold flye so far." The rest of the Kecoughtan scattered. Their abandoned town became English property.20

19Frederick J. Fausz, "An 'Abundance of Blood Shed on Both Sides': England's First Indian War, 1609-1614," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 98 (1990): 3-56.

20Percy, "Trewe Relacyon," 270; Rountree, Pocahontas's People, 54-55.

Meanwhile, De la Warr had been negotiating with Powhatan about runaway English servants. De la Warr did not like that Powhatan's acted so "prowde and disdaynefull," so De la Warr sent George Percy and Captain James Davis to attack the two tribes closest to Jamestown, the Paspahegh and the Chickahominy. Percy went to Paspahegh, where his men burned the Paspahegh's entire town, cut down their nearly ripe corn, killed fifteen townspeople, and captured the weroansqua and her children. As Percy left Paspahegh, his men grumbled that he had spared "the quene and her Children," so Percy threw the children overboard into the James River, "shooteinge owtt their Braynes in the water." Meanwhile, Captain Davis burned a Chickahominy town and its corn fields. When Percy and Davis returned to Jamestown, De la Warr was angry that Percy allowed the Paspahegh weroansqua to live. De la Warr wanted to burn her alive, but Percy had "seene so mutche Bloodshedd that day," that he requested she instead be taken into the woods and stabbed, which she was. The Paspahegh did not recover. Their survivors left to join chiefdoms nearby. As at Kecoughtan, the English now claimed Paspahegh.21

21Percy, "A Trewe Relacyon," 271-73; Rountree, Pocahontas's People, 55; Oberg, Dominion and Civility, 62-63.

It seems irrational that the settlers at Jamestown, who could not and would not feed themselves, went so far out of their way to kill Indians who willingly grew corn for the English. The winter of 1610 was not as harsh as the year before, but the English still had to rely on Indian corn to survive. De la Warr continued to prosecute his war up the James River against Algonquian communities until his health—he suffered from dysentery, gout, and scurvy—forced his retreat, first to Jamestown, and then, in March 1610/11, to England.22

22Ibid.

In May, 1611, the colony's new governor, Sir Thomas Dale, arrived at Jamestown with 300 soldiers to find that no corn had been planted that year and that the people were at "their daily and usuall workes, bowling in the streets."23 Dale set about to repair Jamestown, reform the colony, and defeat Powhatan. Under martial law, Dale forced the settlers to grow and stockpile corn. When Indians attacked the English, Sir Thomas Dale ordered that "by divers and sundry executions, in killing, cutting downe, and takeinge away their corne, burning their houses, and spoiling weares, etc."24 After three years of attacks and counterattacks by both Indian and Englishman, a truce was reached when Powhatan's daughter Pocahontas married the English tobacco entrepreneur, John Rolfe.25

23Ralph Hamor, True Discourse, 26.

24Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:270.

25Rountree, Pocahontas's People, 59-64.

Improved relations lessened the fear of attacks at Jamestown and at Indian villages along the James River. Most settlers moved away from Jamestown to abandoned Indian towns upriver.26 This relocation helped Englishmen to escape the disease and infestation that remained at Jamestown, but it placed a new pressure on Native communities that suddenly had to turn to the English for food. In 1615, John Rolfe noted that the Indians harvest was so poor that "som of their petty Kings have borrowed this last yeare, 4. or 500, bushelles of wheat [corne], for payment whereof this harvest, they have mortgaged their whole Countries."27 This began the process whereby Indians traded their homelands for corn and goods that increasingly became necessary for their survival.

26Earle, "Environment," 112; Morgan, American Slavery, 82.

27John Rolfe, A True Relation of the State of Virginia Lefte by Sir Thomas Dale Knight in May Last 1616 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1971), 6.

The Tobacco Boom and the Second Anglo-Powhatan War

The Englishmen's survival in Virginia seemed more certain by 1615. John Rolfe had just sent his first sample of tobacco to London. It was the first marketable commodity produced in Virginia so far, and immediately, the colonists set to planting tobacco wherever they could find cleared land. To assist, the Virginia Company approved a plan to provide planters with fifty acre grants of land for every immigrant they transported into the colony.

From the outset of Virginia's land grant program there was fraud and scandal that threatened to upset the slender margin by which the colony survived. There were no surveyors in the colony at this time, so most of the patents were inaccurate. Another problem was the tendency for the grantee to add zeros to his grant to increase his share. One claim, for example, was made by a Captain Martin for five hundred, not fifty, acres per share. Martin's claim was contested for years to come. The combined effect of liberal land grants and a tobacco boom placed a new burden on Indian lands where ambitious men could write their own ticket. By 1618, as tobacco prices soared, the English coveted Indians' land more than ever.28

28Wesley Frank Craven (The Southern Colonies in the Seventeenth Century [Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1949]) notes that due to incomplete records, much of Virginia's early land policy must be reconstructed from later action, (121, 122-130); idem., Dissolution of the Virgnia Company (New York: Oxford University Press, 1932), 88.

At the same time, the situation worsened for the Algonquian communities along the lower peninsula. An epidemic hit Virginia in the summer of 1617. Samuel Argall wrote that "a great mortality among us, far greater among the Indians and a morrain [plague] amongst the deer" as well. All life suffered in the Chesapeake that year. The "Indians [were] so poor [they] cant pay their debts & tribute."29 Argall had just arrived as the colony's new governor to discover that most settlers had abandoned their corn fields that flourished under Dale's martial law. Now, they planted the poisonous, profitable sot-weed tobacco instead of life-sustaining corn. Consequently, the English were set to starve come winter.

29Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:92.

The next year was no better. In 1618, there was a severe drought that burnt most of the corn. What little corn survived was then battered by a hailstorm before it ripened. Indian and Englishman alike were in danger of starvation. The bad weather had delayed the relief ship from England until August, but even that ship brought little relief as another epidemic swept Virginia the following year.30

30John Smith, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles, 1624 . In The Complete Works of John Smith (1580-1631), vol. 2, ed. Philip L. Barbour, 25-488 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 263; Rountree, Pocahontas's People ; Morgan, American Slavery .

Amid these near continuous waves of disease and drought, the Virginia Company devised a new plan to sustain its colony, to feed its starved population, and gain firm control of the James River valley. In their "Instructions to Governor Yeardly," dated November 18, 1618, the Company laid the foundation for a more stable colony.31 First, it clarified the colony's land policy. Immigrants who paid for their own passage received a fifty acre grant as a headright upon arrival in Virginia. If they paid for others' passage, then grantees could claim those headrights as well. The headright became the essential element of colonial Virginia's land policy. The promise of fifty acres and the opportunity to possess more stimulated ambitious immigrants to Virginia and pushed settlement farther and farther West, to the fall line of the Chesapeake Tidewater and beyond.32

31Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:98-109.

32Craven, Dissolution 87-89; Morgan, American Slavery, 97-98; Oberg, Dominion and Civility, 68-69.

The Company also established a new government to administer its envisioned expansion. They created a representative government to be centered at Jamestown that consisted of "the Governor, the Counsell of Estate, and two Burgesses elected out of eache Incorporation, & ['Particular'] Plantation."33 Four boroughs were created along the James River to establish representation and to concentrate settlement for trade and defense. From the falls of the James River to its mouth, the boroughs were Henrico, Charles City, James City, and Kecoughtan (renamed Elizabeth City).34 Each borough sent two burgesses to the assembly. The "particular plantations"—"Capt. John Martins Plantn," "Smythes Hundred," "Martins Hundred," "Argalls guisse," "Flower dieu Hundred," Captaines Lawnes Plantation," and "Captain Wardes Plantation"—also sent two burgesses each.35 These plantations were the largest in the colony. For example, Smith's Hundred included over 80,000 acres along the James River. It was organized in 1617 by Virginia Company adventurers Sir Thomas Smith and Edward Sandys, the Earl of Southampton.36

33H. R. McIlwaine, ed., Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 13 vols. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1905-1915), 1:7, 10.

34It should be noted that these boroughs did not function as county organizations in any independent administrative sense.

35McIlwaine, Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1:7.

36Craven, Southern Colonies, 122-29.

When the Virginia Assembly convened in July 1619, one of its first objectives was to encourage "some of the better disposed of the Indians to converse wth our people & to live & labor among them." The assembly instructed planters to employ Indians "in killing of Deere, Fishing, beatting Corne, & other workes" that reflected traditional roles performed by Algonquian men and women in their Native communities. The assembly encouraged Indians to move into the English settlements, although the assembly advised planters that Indians should be housed "apart by themselves, and lone inhabitants by no meanes to entertaine them" and "that a good guard in the night be kept upon them for generally (though some amongst many may proove good) they are a most trecherous people."37 Thus, the central disjunction between Anglo and Indian communities was set. The Virginia Company in London and the new colonial assembly at Jamestown wanted to depend on Indians' labor to feed and support the colony, and it also wanted to segregate Indians from English society to avoid the indiscriminate killing of each by the other.

37McIlwaine, Journal of the House of Burgesses, 1:9-10.

Reverend George Thorpe, who was sent to Virginia by the London Company in 1620, maintained that Indians were human beings worthy of being brought into English society.38 Most, in the colonies and in London, remained generally ambivalent about how to deal with the Natives.

We pray you also to have especial care that no injurie or oppression be wrought by the English against any of the natives of that country, whereby the present peace may be disturbed and ancient quarrels (now buried) might be revived. Provided nevertheless that the honor of our nation and safety of our people be still preserved and all manner of insolence committed by the natives be severely and sharply punished.39

38Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 2:94-95; 3:469, 487; Helen Rountree, "The Powhatans and the English," 188-89.

39Thorpe quoted in ibid..

On the ground, settlers had little use for Indians, and the idea that "the only good Indian was a dead Indian" became a reality. Thorpe summarized the real attitude of Virginians when he said, "There is scarce any man amongst us that doth soe much affoord them a good thought in his hart and most men with theire mouthes give them nothinge but maledictions and better execrations."40 Thorpe was a specific target of the Indians due to his efforts to Christianize their children. In this instance, Thorpe vocalized the frustration of trying to effect Indian policy in the face of conflicting ideologies.

40Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:346; Christian F. Feest, "Seventeenth Century Algonquian Population Estimates," The Quarterly Bulletin of the Archeological Society of Virginia 28:66-79; Rountree, Powhatan Indians, 15.

In this setting, Tidewater Algonquians felt little need to acquiesce to English demands. They did not send their children to live among the English, and likewise, Native peoples successfully resisted English culture. But the English appropriated Indian land, and they segregated Indians from white settlement. From the Indians' perspective, the English had been bad neighbors. In response, on March 22, 1622, Opechancanough led a surprise attack to slow the spread of English settlement up the James River valley and to remind the English of their dependence on the Natives. The Pamunkey war chief and his bowmen struck the English colony and killed 347 colonists of the colony's roughly 1,200 residents.

In response to the attack on English settlement, the English declared "perpetual enmity" against Indians.41 The colonial militia launched annual attacks and seized Indian corn. In fact, for the rest of the 1620s, the colony survived on seized Indian corn. In 1632, a severe drought left little corn for the English to confiscate, and it probably helped end the second Anglo-Powhatan war.42 When peace and rain returned, settlers focused their agricultural endeavors, once again, on their precious tobacco.

41H. R. McIlwaine, ed., Minutes of the Council and General Court of Colonial Virginia, 1622-1632, 1670-1676 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1924), 184-85; Hening, Statutes, 1:140, 141, 153; Craven, "Indian Policy," 73.

42Martha W. McCartney, "Seventeenth Century Apartheid: The Suppression and Containment of Indians in Tidewater Virginia," Journal of Middle Atlantic Archaeology, 1 (1985):56.

To protect the colonists's dispersed plantations and their undefended fields from future Indian attacks, Harvey extended a line of English settlement across the lower peninsula. In 1632, the Assembly offered fifty acres to any man who would settled along this defensive line. When completed in 1633, a six mile palisade stretched from the James River to the York River and enclosed the lower peninsula. This "pale" formalized a pattern of Indian segregation from white settlement that would become a hallmark of the Virginia frontier.43

43Hening, Statutes of Virginia, 1:139-40, 199, 208; Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 8 (1900):157-58; Craven, "Indian Policy," 74; Oberg, Dominion and Civility, 177-79. Williamsburg, at this time, marked the half-way point between the two rivers, hence its name, Middle Plantation.

For as long as the English had been in Virginia, the Natives had dominated the power relationship. In 1608, Captain John Smith counted 2,400 Powhatan warriors, or 13,000-15,000 total inhabitants. By 1624, the Algonquian population may have declined to as low as 5,000.44 Likewise, from December 1606, when the first ships departed England, to February 1624, 6,040 out of 7,289, or six out seven, immigrants to Virginia had died. Between 1621 and 1623 alone, the Virginia Company estimated that over 2,500 colonists' had died from scarcity and disease, while fewer than 350 had been killed in the Opechancanough's attack in 1622.45 The peace of 1633 helped the English to recover their health and their numbers. However, peace did not stop the spread of infectious diseases and noxious Englishmen into Native communities.

44Rountree (Pocahontas's People ) estimates the number of Powhatans in 1624 at 5,000, (78-79). Clearly the first two decades of English settlement devastated Indian populations.

45Bridenbaugh, Jamestown, 48-49. John Camden Hotten, The Original List of Persons of Quality ... and Others Who Went from Great Britain to the American Plantation, 1600-1700 (London, 1874), 201-65; Wesley Craven, Red, White, and Black: The Seventeenth-Century Virginian (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1971), 3.

The Third Wave: English Settlement and Anglo-Indian War

The Virginia colony had been at peace with the Powhatan chiefdom since 1633. Sir John Harvey, the governor and captain general of Virginia who crafted the delicate peace, understood the need to expand the Virginia frontier and secure it from those Natives whose homes the Virginians had destroyed. In this mix of frontier expansion and defense, divisions arose between provincial authority and local government. At the top, the governor sat as the crown's representative. The colony's leading men were the governor's council. They were principals in the administrative, political, and financial success of the colony. Beneath them was the House of Burgesses, a body of leading men elected by the freeholders of the colony. The burgesses came from the counties most influential families, and they confirmed the governor's appointees to the local courts. The county court system was designed "to do justice in the redressing of all small and petty matters."46

46"A Brief Description, etc.," Colonial Records of Virginia, (State Senate Doct. Extra, 1874), 81, quoted in Philip A. Bruce, Institutional History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century, 2 vols. (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1910), 1:485.

In 1634, in response to rapid population growth and territorial expansion, Governor Sir John Harvey expanded the local court system to provide additional local administrative and political authority. He created eight counties along the lower peninsula (between the York and James rivers) and south of the James River.47 Harvey designated the region between the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers as the Chicacoan district. Harvey hoped to keep the district free of English settlers and avoid another Indian uprising like the one that devastated the James in 1622. For the next fifty years, the county government influenced the local planter more immediately than did the provincial government at Jamestown.48 This frequently pitted the governor against the county courts, where the Burgesses mediated. Yet the governor was so opposed by the councilors, who, in 1635, "thrust out" Governor Harvey because his conservative, orderly vision of expansion did not correspond to the territorial aggrandizement expected by leading and powerful councilmen, burgesses, and local landowners.49

47Hening, Statutes, 1:223; Craven, Southern Colonies, 169. East from the falls of the James River, the counties were Henrico, Charles City, James City, Warwick River, Charles River (York), Warrosquyoake, and Elizabeth City. The eighth county, Accomac, was on the Eastern Shore.

48Warren M. Billings, "The Causes of Bacon's Rebellion: Some Suggestions," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 78 (October 1970), 411; Oberg, Dominion and Civility, 187.

49For Harvey's "thrusting-out," see J. Mills Thorton, III, "The Thrusting-Out of Governor Harvey: A Seventeenth Century Rebellion," VMHB 76 (1968); Oberg, Dominion and Civility, 176-79. For a thorough discussion of Virginia's governmental structure in the seventeenth century, see Bruce, Institutional History, 1: 463-646 (County Courts); 2: 374-390 (Council), 403-521 (House of Burgesses). Craven, Southern Colonies .

Sir Francis Wyatt returned as interim governor, on January 12, 1640/1. His return signaled a renewed expansion of English plantations as the Grand Assembly of Virginia voted to open the Rappahannock River for settlement the following year.50 The assembly set the entry price high enough to prevent excessive settlement. Each patentee had to purchase at least 200 headrights with at least six "able tithable persons in every family that there sit down."51 At fifty acres per headright, each patentee would be required to seat 10,000 acres, and before that could be done, the patentee had to demonstrate that he had entered into a formal "Compound with the Native Indians whereby they [both Indian and Englishman] may live more securely."52 By 1642, when the measure took effect, Sir William Berkeley, Virginia's new governor and captain-general, had arrived. At the June assembly, Berkeley tried to undo this act entirely. He failed outright to stop new patents but succeeded to keep unseated those new patents in the Rappahannock valley. The assembly reserved that "it should and might be lawfull for all persons to assume grants for land there [north of the Rappahannock River]," provided that the land be seated only with the assembly's approval. To encourage rampant speculation on the Rappahannock River, the assembly allowed that, unlike the rest of the colony, patents along the Rappahannock could be made "without exact survey."53

50Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 9:53.

51Ibid.

52Ibid.

53Hening, Statutes, 1:274, marks the re-enactment of the legislation in March 1642/43.

Within two months, John Carter made the first land patents along the Rappahannock River. On August 15, 1642, Carter patented 1,300 acres near the mouth of the Rappahannock River along its north bank near its junction with the Corrotoman River. Carter was a burgess from Upper Norfolk County who lived on the Nansemond River south of the James River.54 On November 4, 1642, his Nansemond neighbors, councilman Richard Bennett, William Durand, and Captain Daniel Gookin patented a 4,200 acres, thirty-five miles up the Rappahannock River.55 The Bennett and Durand patents were on the south side of the river. Durand's patent included the Indian town Neincoucs, which was perhaps a former Opiscopank town. Gookin's patent was on the north side, directly across river from Bennett and Durand and very near the Moraughtacund capital town on Morratico Creek.56 None of these patents were seated, but each patentee anticipated that the Indians would soon abandon their towns as they had done on the lower peninsula and south of the James. The English coveted Indian towns the most because abandoned villages meant cleared home sites for English settlement, open fields for English crops, and clear paths to the next Indian town.

54Nell Marion Nugent, Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia's Land Patents 4 vols. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1934-1979), 1:132.

55Ibid., 1:138-39. Bennett patented 2,000 acres, Durand patented 800, and Gookin patented 1,400.

56Thomas Warner, History of Old Rappahannock County Virginia 1656-1692 (Tappahannock: printed privately, 1965), 14. The Bennett-Durand property line later became the boundary between Old Rappahannock (1656) and Middlesex Counties (1669).

Continued tension between Indian and Englishmen in the lower Tidewater caused Opechancanough, in 1644, to lead a second attack to check English expansion up the lower peninsula, beyond the Middle Plantation line.57 Opechancanough's confederates killed nearly 400 colonists. The Virginians struck back against all Indians for they assumed that all were guilty. In June 1644, the Council began to plan their northern neck campaign against the Indians. Without real consideration that the tribes there may not have joined in Opechancanough's attack, the Council voiced strong support for action, except for councilor William Claiborne, whose "opinion [was] different from others in relation to the propriety of War upon the indians between the Rappahannock and Potomac."58 The pitch for revenge was so great that Claiborne's dissent was noted only in passing. The Council went ahead with their war plans, and on September 3, 1644, voted to attack the Rappahannock's corn.59 No record exists of the attack, and it is likely that Claiborne's "opinion" gained favor over the winter as the Council realized the advantage it could gain by cultivating good relations with Algonquian communities along the Rappahannock River while making war plans against Opechancanough.

57Oberg, Dominion and Civility, 180-81; Frederic W. Gleach, Powhatan's World and Colonial Virginia: A Conflict of Culture (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), 73-84.

58McIlwaine, Minutes of the Council and General Court, 501.

59Ibid., 502.

Accordingly, on February 26, 1644/5, as the Council prepared for another march against Pamunkey, it also sought "the service of some Indians either of Achomack [eastern shore] or Rappahannock [to] be treated with and entertained for further discovery of the enemie."60 To secure a Rappahannock alliance, the Council commissioned Captain Claiborne to "treat with the Rappahannocks or any other Indians not in amity with Opechancanough, concerning serving the county against the Pamunkeys"61 Guided by these Native scouts for the next two years, the English struck with a vengeance at the heart of the Pamunkey's Algonquian alliance. They attacked the Powhatan towns, seized their crops, burned their towns, and dislodged them from the James and York river valleys. The defeated Powhatan chiefdom concluded a general peace with Virginia and its governor, Sir William Berkeley.62 The defeat of this paramount chiefdom meant the degradation of all Virginia's Native people.

60Hening, Statutes, 1:293. This is a clear indication that the Rappahannock were not part of Opechancanough's paramount chiefdom and did not take part in the uprising.

61McIlwaine, Minutes of the Council and General Court, 563.

62Hening, Statutes, 1:323-26.

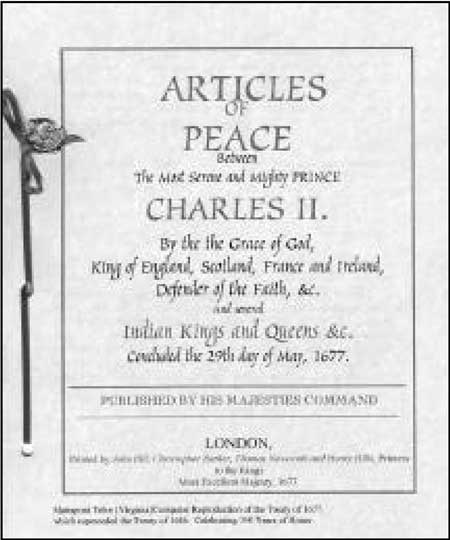

In 1646, the Englishmen in Virginia succeeded in their four-decade effort to reduce the Algonquian chiefdoms of Tsenacomoco to tributary status.63 The articles of peace dated October 5, 1646, asserted English rights of conquest over all Virginia Indians.64 Defeated, the paramount chief, Necotowance, now held his dominions as a vassal of the English king. He acknowledged the sovereignty of the English crown and agreed to pay an annual tribute of twenty beaver skins.65 While not a substantial tribute, it was an annual recognition of the crown's dominion, and it was an annual reminder of the responsibilities and rights that tributary status conveyed. Among the responsibilities, the tributaries were required to gain English approval for tribal leaders. More importantly, all Indians were required to vacate the region between the James and York Rivers from Kecoughtan (the tip of the lower peninsula, or, modern day Hampton, Virginia) northwest to the fall line.66

63The Indians in Virginia were called "tributaries" after they were defeated militarily and required by English law to pay an annual tribute to the crown

64Rountree (Pocahontas's People, especially Chapter Five, "A Declining Minority," 89-127) asserts that 1646 marks the beginning of Powhatan decline. For Virginia Indian policy through 1662, see Craven, "Indian Policy," 65-82. For the legal status of Virginia Indians, see W. Stitt Robinson, "The Legal Status of the Indians in Colonial Virginia," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 61 (July 1953):247-59. Robinson traces three classes of Indians—tributary, foreign, and individuals living as freemen in the colony without tribal ties—for Virginia's entire colonial period. A subsequent article by Robinson ("Tributary Indians in Colonial Virginia," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 67 [January 1959]:49-64) examines tributaries exclusively but concludes that the "mutual benefit evident in the tributary system in Virginia modifies, if it does not refute completely, the glib generalization—in which even scholars occasionally indulge—that for the English the only good Indian was a dead Indian," (64).

65Later tributary treaties changed the specific tribute due—animal pelts, arrows, fish, deer, and fowl—but importantly, a tribute is still paid to the governor every Thanksgiving.

66Hening, Statutes, 1:323-24.

The English were now the sole occupants of the lower peninsula. No Indian could "repaire to or make any abode upon the said tract of land, upon paine of death, and that it shall be lawfull for any person to kill any such Indian,"67 Points of entry were established at Fort Royall (for the north side—Pamunkey River) and Fort Henry (for the south side—Appomattox River), and Indian messengers had to obtain a permit and a striped coat, which verified the authority of the permit, to travel within this region. In effect, only authorized Indians could enter the area of English settlement. This treaty expanded the cultural and legal segregation of Indian from English, which contradicted the Anglo-Virginians stated desires to remake Indians as Englishmen.

67Ibid.

Necotowance was to encourage the Indians to send their children, "not above twelve yeares old," to live with the English.68 Tributary children, especially, were desired as servants. This demonstrates the extent to which the English would go to obtain free labor. By assimilating the children and keeping captive Indians as slaves, Virginians hoped to break traditional Algonquian social influences—of family and religion—and thus, remake Indians in English ways.69

68Ibid., 326.

69For the earliest plan to convert Indians, see "Instructions Orders and Constitucons to Sr Thomas Gates Knight Governor of Virginia, May 1609," Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:14-16.

Of course these responsibilities were not without rights. The tributaries were guaranteed military support against their enemies, and it is in this sense that this relationship is viewed as an alliance. The proximity between white and Indian settlement meant that it was in the colony's interests to defend the tributaries from attacks by "foreign" Indians. The principal right given to the tributaries was the freedom to inhabit the north side of the York River without interference from the English, excepting those parts that were already settled, from Poropatanke downward, or, the southern tip of the middle peninsula, that is, Gloucester County. The 1646 treaty outlined the pattern of expanding white settlement and demonstrated English desires to ensure that settlement continue in a peaceable manner. Given peace with the Algonquians, immigration to Virginia increased, the English population grew, and the 1646 treaty facilitated settlement among tributary Indians.70

70The best account of this demographic shift is Morgan, American Slavery, 133-57. For greater use of quantitative data, see Richard S. Dunn, "Servants and Slaves: The Recruitment and Employment of Labor," in Colonial British America: Essays in the New History of the Early Modern Era, 157-94, eds., Jack P. Greene and J. R. Pole (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984). Craven, "Indian Policy," 76-77.

Indians were left to inhabit lands north of the York River, where the English were prohibited from going except to recover their property (i.e, runaway servants). The treaty with Necotowance was Act I of the 1646 legislative session. Act VI, presumably passed not too much later—hours or days—opened settlement north of the York River.71 Certainly this raises questions as to the Assembly's sincerity in protecting Indian's land. The Assembly's efforts were never intended to defend Indians for long against ambitious settlers. Thus, the pattern was confirmed. Military defeat gave way to greater expropriation of Indian land by Virginians who were not content to remain south of the York River, or for that matter, south of the Rappahannock River.72

71Hening, Statutes, 1:323-26, 329; Rountree, Pocahontas's People, 87.

72Despite continued English encroachment north, there was relatively little movement west. This is due to at least two factors. First, the Indians that lived west of the fall line were notably more hostile. Their warring ability explains, in part, why Powhatan had not extended his empire beyond the fall line. The English had yet to secure all of Tidewater Virginia. By contrast, northern expansion was facilitated by numerous rivers and creeks.

Shortly after the York River was opened for settlement, the rich farmland there was patented. In every instance, the protection of Indian land was subsumed to white demands for land. Plantations were established in the Rappahannock and Potomac basins, which were still legally off-limits to Englishmen. Eager to gain huge tracts of riverside land, rapacious Virginians paid little attention to the law. In an attempt to reduce the hostility between Indians and Englishmen, the Virginia Assembly was forced to protect Native rights to their land. In 1652, the Assembly passed an act stating that there would "be no grants of land to any Englishman whatsoever de futuro until the Indians be first served with the proportion of fiftie acres of land for each bowman."73 The measure demonstrates the attempt by provincial authorities to codify and regulate Indian land rights. At the same time, that codification was defined in English terms: fifty acres was the headright received by importers for each indentured servant that entered the colony.74 By apportioning land at the same rate for Indians and Englishmen, the Assembly created an "Indian headright" and actuated a plan to remake the tributary Indians as subsistence farmers. Thus, control of land and the drastic reduction of Indian territory became a primary means through which Indian identity was altered.

73For successive patents see Nugent, Cavaliers and Pioneers, 1:324,353, 362, 407, 457, 505. For legislation that guaranteed fifty acres for each bowman see Hening, ed., Statutes of Virginia, 1:382, 456-7.

74Anyone who settled in Virginia received a headright of fifty acres. In the case of indentured servants, that headright was conveyed to the person who funded their passage. See Kingsbury, ed., Records of the Virginia Company, 3:100-1, 107; Morgan, American Slavery, 94. For the 1660 to 1705 period, see ibid., 328-37. Morgan lays out the legal status of Virginia Indians to illustrate their role in Virginia's labor system as servants and slaves. My interpretation differs from Morgan, in that, I connect the legal status of Indians to English efforts to create a biracial society.

An Act for Civilizing Indians

On March 10, 1655/6 the Virginia Council passed another plan for civilizing Indians. A central component of this act was the introduction of Indian severalty, or separate property, to the tributaries. First, to combat the wolves that threatened settlers and livestock alike, the Assembly granted to the tributaries one cow for every eight wolf heads delivered to county officials. It was asserted that "this will be a step to civilizing them and making them Christians."75 The connection between cattle and Christianity is clear in that animal husbandry was a component of settled agriculture, which (by English standards) was necessary for both Christianity and civilization to take root.76 Implicit here were metropolitan desires to reconstruct the Algonquian economy along English lines.

75The following year (March 1657/8), the colony-funded wolves for cows plan was scrapped in favor of a county-funded wolves for tobacco plan. See Hening, ed., Statutes of Virginia, 1:456.

76Nicholas Canny, "Ideology of American Colonization: From Ireland to America," William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd. ser., 30 (October 1973): 585-6.

While colonial officials were content to influence adult Indians through economic means, they sought to remove Indian children from their native environment and educate them as Englishmen. The second part of this plan restated the education policy laid out by the provisions of 1646 tributary treaty. The Assembly maintained that if "the Indians shall bring in any children as gages of their good and quiet intentions to us and amity with us, then the parents of such children shall choose the person to whom the care of such children shall be intrusted and the country by us their representatives do engage that we will not use them as slaves, but do their best to bring them up in Christianity, civility and the knowledge of necessary trades."77 In effect, these children were hostages ("gages of their good and quiet intentions") designed to ensure the tributaries good behavior. The daily reality was that children were servants, a source of labor.

77Hening, ed., Statutes of Virginia, 1:396. This measure was written into 1646 treaty and had been restated in March 1654/5, see ibid., 410.

The Protection of Indian Lands

Concurrently, the colonial legislature enacted measures to ensure some form of protection for Indians against unscrupulous land deals. All sales of Indian land had to be approved by the Assembly.78 This measure did little else than ease the tensions of the present situation. It did nothing to address English land practices, and by 1658, the Assembly had to reaffirm the 1652 provision guaranteeing fifty acres for each bowmen.79 This guarantee of land—a de facto reservation—while formally acknowledged by the Council, did not last for long. English encroachment continued despite repeated rulings to secure Indian land rights.

78Ibid., 396.

79Ibid., 456-7.

Anglo-Virginians never doubted the eventual demise of Indian land titles, and they believed that fair legislation both ensured the peaceful transfer of land and kept tributaries within Virginia's settled boundaries—a defensive measure that was necessary for the Virginia plantation to survive. Remember, that according to the 1646 tributary treaty, the Algonquian chiefdoms and the English had a military alliance, and despite English efforts to segregate Indians from whites, the tributaries, reduced numbers notwithstanding, remained an essential defensive component of frontier settlement. In truth, Algonquian decline was real, and by 1669 the tribal populations had fallen by over 60 percent.80 These losses were due to epidemic disease and warfare and resulted in weakened Algonquian communities. Increasingly, the English perceived the tributaries as less "savage" and more dependent—objects to be pitied, not feared.

80In 1669, the colony counted 725 Powhatan warriors. This translates into rough population of 4,000. See Hening, ed., Statutes, 1:274-75.

A Changing Native Culture

As tributaries, the Powhatan's began to lose the "savage" personae that Englishmen felt typified the Indian. The tributary Indians continued to pose a danger to Virginia settlement, but Indian attacks during this time were directed at specific individuals, not on the colony as a whole. The Algonquian threat, when compared to non-tributary, "foreign" Indians, had been greatly reduced.81 Evidence of this decline is apparent in the language of a 1663 act addressed to "Northerne Indians." This specific measure was aimed at the Potomacs, but the message was clear for Doeg, Piscattaway, and Susquehannock, all of whom lived north of the Potomac River, continually raided English plantations, and threatened expansion on the Northern Neck.82 The language in this measure was harsh and precise:

[D]eliver such hostages of their children or others as shall be required; and if they or any of them shall refuse to deliver such hostages as shall be required, that the nation to be declared as an enemy and proceeded against accordingly ... . And as we have endeavoured for the future to provide for the safety of the country that such hostages be delivered as shall be required, soe it is also enacted that the hostages to be delivered shall be civilly used and treated by the English to whose charge they shall be delivered, and that they be brought up in the English literature (soe far as they are capable).83

81This owed both to a reduced Indian population and a tremendous increase among Anglo-Virginians. The numbers are telling: In 1640, Virginia's population was 8,000; by 1650 it had nearly doubled to 15,000; ten years later it approached 40,000.

82The Northern Neck is the peninsula that lies between the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers.

83Ibid., 2:193-4.

Contrast this with the language used for the tributaries in 1656 where Indian children were "gages" of their parents' "good and quiet intentions."84 The images are similar in that children were seen as the means through which Indian society must be recreated. The differences arise in how each was conveyed. For the tributaries, children were "gages"; for hostile Indians, children were "hostages" who would be educated "soe far as they are capable."

84Ibid., 1:396.

Despite this apparent distinction in degrees of perceived savagery, colonial legislators agreed that Indians were to have equal justice with whites.85 This demonstrates, in some sense, that the English understood that civilizing Indians was a process. Indians were afforded legal rights equivalent to whites because, at this time, Virginians conceived of Indians more in ethnic-class terms than in racial ones.86 In that, Indians had equal access to the law, especially those who converted to English ways.

85Ibid., 2:194.

86Edmund Morgan (American Slavery ) argues that white racism toward blacks grew out of white hatred of Indians. He writes that by 1676 the whites "were doubtless prejudiced against blacks as well and perhaps prejudiced in a somewhat greater degree than they were against Irishmen, Spaniards, Frenchmen, and other foreigners. The Englishmen who came to Virginia, of whatever class, learned their first lessons in racial hatred by putting down the Indians," (328).

Detribalized Indians

The English wished to detribalize the Virginia tributary Indians.87 For most of the seventeenth century it was possible for a detribalized Indian to enter the lower or lower-middle levels of white English society. For this period, however, there is only one extant record of a detribalized Indian participating in white society.88 In 1665, Edward Gunstocker, or "Indian Ned," of Nanzatico patented 150 acres on the north side of the Rappahannock River. His patent was approved by Governor Berkeley but only after he had paid headright for three Englishmen to come to Virginia.89 Apparently, Indian Ned developed an equitable relationship with local Virginians and for a time tried to mediate Indian-Anglo disputes in the lower Rappahannock basin.90 By March 1666, however, opposition from his own tribe necessitated that he be put under English protection.91 During Bacon's Rebellion, Gunstocker joined the English in their war on the Indians. He made a will leaving everything to his wife Mary, whose ethnic identity is unknown.92 Again, this is the only extant record of a detribalized Indian in the seventeenth century, and it suggests both reluctance on the part of Indians to leave their cultural roots and tribal identity and establish themselves in English culture and an unwillingness on the part colonists to accept such Indians in white society.

87Rountree, Pocahontas's People, 135.

88In all likelihood there were several Indians who detribalized. The problem here is that records from the counties with the largest concentration of Indians (namely New Kent) were destroyed by fire during the Civil War.

89Nugent, 1:566; Conway Robinson, "Notes from the Council and General Court Records, 1641-1682," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 8:64-73, 162-70, 236-44, 407-12 237.

90Old Rappahannock County, Deeds, 2:201-202 (printed in William and Mary Quarterly, 2d ser., 18:297-98); "Stafford County Records, 1664-1668, 1689-1693," Virginia Magazine of History Biography 44:192; Rountree, Pocahontas's People, 95).

91Old Rappahannock County, Deeds, 3:257-8 (printed in William and Mary Quarterly, 2d ser., 16:590).

92Old Rappahannock County, Deeds, 6:76 (printed in William and Mary Quarterly, 2d ser., 16:593).

Tributary Indians

Just as Virginians moved to secure the legal rights of detribalized Indians, they reinforced their dominion over the tributaries. In October 1665, the Virginia Assembly passed a series of measures designed to further regulate tributary actions. It appointed Indian commissioners for each county to oversee Indian affairs. The assemby also restricted tributary sovereignty and eliminated each group's power "to elect or constitute their owne Werowance or chief commander."93 This differed from the 1646 provision: in the earlier instance, the tribe retained the power to nominate leaders who were then approved, or rejected, by the governor of Virginia. The 1665 measure arbitrarily transferred the power of appointment to the governors-general who "shall constitute and authorize such person in whose fidelity they may finde greatest cause to repose a confidence to be the commander of the respective townes."94 In this manner, the English continued their attack on Indian sovereignty.

93Hening, Statutes, 2:219.

94Ibid.

"Lives and Liberties"

Joined to this act was a proviso that stated if an Englishman was murdered, "the next towne shalbe answerable for it with their lives or liberties to the use of the publique."95 This pointed the way to a pattern of increased dominance whereby Indians were made answerable "to the use of the public." In real terms, this policy justified the wholesale removal of Indians from their land, and the sale of those Indians into involuntary servitude, if not outright slavery. This raises the specter of Indian servitude and slavery.

95Ibid.

It had been the policy of the Virginia Assembly to extend servitude to Indians as a means of bringing them to English civility. At the same time, chattel slavery increased as Virginia's labor needs grew beyond what the servant headright system could incorporate. This was particularly true after 1660. While the new slaves were predominantly black, there were a considerable number of Indian slaves — imported from the Carolinas — living in Virginia.96 To regulate Indian slaves' interaction with white-Virginia, the colony passed laws designed to regulate the personal aspects of Indian life. While frequently directed at "servant" Indians, these laws were applied generally to all Indians.

96It is important to understand the premium that Virginians placed on labor. To exploit resources in Virginia, settlers depended heavily upon imported labor. Initially they relied upon indentured servants. High mortality rates and an expanding economy made social mobility a real possibility. By mid-century a drop in tobacco prices combined with increased production and decreased mortality rates resulted in a large class of restless men who kept Virginia in a constant state of turmoil. This unrest culminated in Bacon's Rebellion, which, in addition to addressing real political grievances, was centered on issues of race and class.

In 1670 the Assembly considered the status of Indian laborers. After debating whether Indians sold in Virginia by other Indians (who captured them in tribal wars) should be slaves for life or for a term of years. At the time it was decided that servants who were not Christians and who were brought into the colony by land (Indians from other regions) should serve for twelve years or (if children) until thirty years of age. The same act stated that non-Christian servants brought in "by shipping" (Negroes) were to be slaves for life. Thus Africans purchased from traders were assumed slaves but Indians were not. In 1682 the Assembly eliminated the difference, making slaves of all imported non-Christian servants.97

97Long quote from Morgan (American Slavery, 329) is based on Hening, ed., Statutes, 2 :283, 490-92.

Model Virginians

In 1670, Governor Berkeley reported that there were 6,000 indentured servants and 2,000 slaves in Virginia. The question remains, then, what happened between 1670 and 1682 that precipitated the shift from white indentured servants to non-white chattel slavery and, in the process, so hardened attitudes toward Indians? The answer is Bacon's Rebellion, an event that signaled the demise of English efforts to remake tributary Indians as Englishmen and inaugurated a series of laws that further isolated Indians socially and categorized them racially as non-white. This divergence is best realized by tracing the lives of Baconian partisans, with a particular emphasis on William Byrd I. Byrd was a supporter, first of Bacon, and, then, of those royalist forces who crushed the rebellion, sacked the inept and inefficient Berkeley oligarchy, and paved the way for a royalist resurgence in Virginia. Byrd is exemplary here because he survived the events of 1676 and by the end of the century was the most powerful planter in Virginia—a model of imperial acculturation.

William Byrd, the Elder

William Byrd I arrived in Virginia in 1669 at the age of seventeen. This son of a London goldsmith was the apprentice and sole heir to his maternal uncle Colonel Thomas Stegge, Jr.98 Stegge, who had been the colony's auditor-general since 1664, was the son of Thomas Stegge, Sr., a commissioner to the county court of Charles City and a member of the Virginia Council from 1642 until his death in 1652.99 The younger Stegge died in 1670, and his widow, Sarah, married Lt. Colonel Thomas Grendon, also a commissioner to the county court of Charles City.100 The establishment of this lineage is significant for it lays out the potential for antipathy that existed between Byrd and Berkeley in that the elder Stegge supported the Commonwealth government against the royalist Berkeley and that the younger Stegge's widow was one of the most vocal anti-Berkeleyans.

98The First Gentlemen of Virginia: Intellectual Qualities of the Early Colonial Ruling Class (San Marino: Huntington Library, 1940), Chapter 11, "The Byrds' Progress from Trade to Genteel Elegance," 312-47. Considerably more has been written about Byrds' son and grandson, William Byrd II and III.

99Craven, Southern Colonies, 268 n16. The elder Stegge was lost at sea in 1652 while returning from England as a commissioner to the Commonwealth government. He was carrying orders "for the reduction of the Virginia colony," (259) and the removal of Berkeley. Needless to say, Berkeley was not endeared to the Stegge family.

100Sarah's opposition to Berkeley was well known throughout the colony. See Stephen Saunders Webb, 1676: The End of American Independence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984; reprint, Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1995), 5, 6, 20-21, 106, 157.

From Stegge, Byrd inherited a plantation in Henrico County complete with a storehouse of goods for trade with the Indians. Stegge, along with Edward Bland and Abraham Wood had extended trade relations to the south and west, first through the Occaneechee and later with the Cherokee across the Appalachians. When Byrd arrived, Wood maintained the trade monopoly, but Byrd quickly established himself as a master of Indian affairs and was "regarded as a future successor of Colonel Wood."101

101Pierre Marambaud, "A Young Virginia Planter in the 1670s," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 133.

Nathaniel Bacon, the Younger

In 1674, Nathaniel Bacon, the younger, arrived in Virginia with equally favorable connections to gentility but more favorably received by Berkeley than Byrd had been. Bacon was described as

about four or five and thirty years of age, indifferent tall but slender, black haired of an ominous, pensive, melancholy Aspect, of a pestilent & prevalent Logical discourse tending to atheisme in most companyes, not given to much talke, or to make suddain replyes, of a most imperious and dangerous hidden Pride of heart, despising the wisest of his neighbours for their Ignorance, and very ambitious and arogant.102

102"The Royal Commissioners' 'Narrative of Bacon's Rebellion," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 4 (October 1896): 122. This description of Bacon was given after the rebellion, and they adjectives used to describe him are probably tainted by his actions. Regardless, this excerpt provides valuable insight into Bacon's character as a shrewd and ambitious. Bacon's impatience with neighbors was no doubt indicative of his feelings toward the antiquated Berkeley and his oligarchical cohort.

Bacon's ambitions and pride were not satisfied in Virginia despite being elevated to the Council soon after his arrival. In keeping with Berkeleyan tradition, he was afforded this opportunity as he was cousin to both Lady Berkeley and the councilor Nathaniel Bacon, Sr. He quickly staked out land for himself in Henrico County not too far from Byrd. Both plantations were at the outer edge of the frontier, and Bacon developed a keen interest in the lucrative Indian trade. In September 1675, Byrd and Bacon offered to purchase the Indian trade monopoly held by Wood from Berkeley but were rebuffed.103

103Wilcomb Washburn, The Governor and the Rebel: A History of Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1957), 17-19.

"A War against All Indians"

Earlier that summer (July 1675) on the Northern Neck, a dispute arose between Thomas Mathew and a band of Doeg Indians living in Maryland. The Doeg claimed that Mathews had cheated them in trade. As retaliation, they raided Mathews' plantation and took some of his hogs.104 In response, Mathew gathered several of his neighbors and pursued the Indians. He caught up with them, beat some and killed others, and reclaimed his hogs. Again, the Doeg retaliated, this time killing two of Mathew's servants and Mathew's son.

104Virginians, then as now, take their pork very seriously.

Following this, the Northern Neck militia under Giles Brent and George Mason set off in pursuit of the murdering Doeg. In their search, Brent came across a Doeg village, he questioned the weroance, who denied any knowledge of the event, and when the weroance tried to run away, Brent shot him. A firefight ensued and another ten Indians were killed. Mason, who in the meantime had split off from Brent's forces and surrounded some Indians in their cabin, heard the gunfire. The Indians inside the cabin heard the engagement as well and when they rushed out, Mason's militiamen opened fire killing fourteen Indians. Mason realized that the Indians he had killed were Susquehannocks, a nation who maintained peaceful relations and a lucrative trade with Virginia.105

105"Mathew's Narrative," in Charles M. Andrews, ed., Narratives of the Insurrections, 1675-1690, (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1915), 17.

In the confusion that followed, Berkeley sent John Washington and Isaac Allerton to investigate.106 Unable to locate the Doeg, who by this time had dispersed into the backcountry, Washington and Allerton rendezvoused (in late September) at the Maryland fortress occupied by the Susquehannock. There, they met the Maryland militia under Thomas Truman, and it was decided that they would lay siege to the Susquehannock fort. During the siege, five Susquehannock sachems came out to negotiate with the Virginians and the Marylanders, but the English "caused the [Indian] Commissioners braines to be knock'd out."107 The siege continued, and in mid-October the Susquehannock (some 1,000 strong) crept out of their fort while the English slept.

106Westmoreland County Records, Deeds and Wills, fol. 232, printed in William and Mary Quarterly, 1st ser., 4 (1895-1896), 86.

107"The History of Bacon's and Ingram's Rebellion," in Andrews, ed., Narratives, 47-48, quoted in Oberg, "Dominion and Civility," 424.

The Susquehannock crossed the Potomac resolving "to imploy there liberty in avenging there Commissioners [sachems] blood, which they speedily effected in the death of sixty inossescent souls."108 Afterwards, the Susquehannocks, displaced from their land base in Maryland, "moved over the heads of Rappahannock and York Rivers, killing whom they found on the upmost Plantations until they came to the head of the James River, where ... they slew Mr. Bacon's Overseer whom He much Loved, and of his Servants, whose Blood Hee Vowed to Revenge if possible."109 According to Berkeley, "that barbarous Nation kild about six and thirty men, women and children in the freshes of the Rappahannock River, and since that they kild two men at Mr. Bird's House."110 Both Byrd and Bacon suffered the depredations of Indian warfare on the frontier. It mattered little to them or their fellow frontiersmen that the murder of white Virginians was caused by the impetuosity of their white neighbors on the Northern Neck.

108"Cotton's Narrative," in Peter Force, ed., Tracts and Other Papers Relating Principally to the Origin, Settlement, and Progress of Colonies in North America, 4 vols. (Washington D.C.: Peter Force, 1835), 1: no., 9, 3, quoted in Oberg, "Dominion and Civility," 424.

109"Mathew's Narrative," in Andrews, ed., Narratives, 19-20.

110Governor Sir William Berkeley to Thomas Ludwell, April 1, 1676, Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 20 (July 1912): 248.

Not long after, Byrd and Bacon gathered with other Henrico planters to discuss their frontier predicament.

Now this man being in Company with one [James] Crews, Isham and Bird, who growing to a highth of Drinking and making the Sadness of the times their discourse, and the ffear they all lived in, because of the Susquehannocks who had settled a little above the Falls of the James River, and comitted many murders upon them; among whom Bacon's overseer happen'd to be one, Crews and the rest persuaded Mr. Bacon to goe over and see the Soldiers on the other side of the James river and to take a quantity of Rum with them to give the men to drinke, which they did, and (As Crews &c. had before laid the plot with the Soldiers) they all at once in field shouted and cry'd out, a Bacon! a Bacon! a Bacon! which taking Fire with his ambition and Spirit of ffaction & Popularity, easily prevail'd on him to Resolve to head them, His Friends endeavouring to fix him the ffaster to his Resolves by telling him that they would also go along with him to take Revenge upon the Indians, and drink Damnation to their Soules to be true to him, and if hee could not obtain a Commission they would assist him as well and as much as if he had one; to which Bacon agreed.111

111Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 4 (October 1896): 122-5.

It made little difference that immediately after the Susquehannock had exacted their revenge for the murder of their chiefs, they appealed to Berkeley to conclude a peace.

The governor first rejected the Susquehannock overtures and called out the militia to march against the murdering Indians. Then, Berkeley countermanded his order and disbanded the militia.112 As late as spring 1676, Berkeley had not acted, and the frontier counties, namely Henrico, New Kent, and Surry, were on the verge of revolt. The frontiersmen wanted the authority to appoint Bacon as their commanders and pursue the Susquehannock, but Berkeley refused.

112British Public Records Office, Colonial Office, 5/1371, 189, in Oberg, "Dominion and Civility," 425.

Ignoring the governor's demands, Bacon proceeded, with the encouragement of Byrd, to make preparations and gather men to attack the Indians. Baconians were comprised largely of propertied men with land and power and freemen with neither.113 Both groups lived on the frontier and were faced with the revenge of "foreign" Indians for injuries done them by frontier militias and the arbitrary acquisition of their lands by colonists. The Baconians rise to power was precipitated by their demands for a war "against all Indians in general for that they were all Enemies."114 Additionally, Baconians were united by a general feeling that Virginia's antiquated oligarchy, with Berkeley at the helm, was unconcerned with their needs and unresponsive to their calls for a war against all Indians.115 In short, Bacon wanted to eliminate the northern tribes who had been ravaging the frontier in response to increased white encroachment; to eliminate those tribes within the settled regions of Virginia in order to gain access to their rich lands that could be used for agricultural production; and to eliminate the Occaneechee as a way of destroying Berkeley's control of frontier Indian trade to the West and the South.

113Several interpretations of Bacon's Rebellion have prevailed. For its race and class connections, see Morgan, American Slavery, 250-70. T. J. Wertenbaker (Torchbearer of the Revolution Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1940]) offers a pro-Bacon perspective while Washburn (Governor and Rebel ) favors Governor Sir William Berkeley. For the rebellion's imperial implications, see Webb, 1676, 3-165, 409-16.

114"This," Bacon reported, "I have alwayes said and doe maintain." See Nathaniel Bacon to William Berkeley, Coventry Papers, 67:3, quoted in Morgan, American Slavery, 255.

115Webb, 1676, 21-25.

The political dimension of Bacon's actions was centered around Berkeleyan social and political control. There was resistance by "substantial planters to the privileges and policies of the inner provincial clique led by Berkeley and composed of those directly dependent on his patronage... . Their discontent stemmed to a large extent from their own exclusion from privileges they sought."116 The principal objective in attacking the Indians, aside from the belief that the only good Indian is a dead one, was to lash out at Berkeleyan elites. The two principal recipients of Baconian revenge were the Occaneechee (Berkeley's primary trading partners) and the Pamunkey (Berkeley's principal tributary tribe and historic leader of the Powhatan paramount chiefdom).

116Bernard Bailyn, "Politics and Social Structure in Virginia," in Colonial America: Essays in Politics and Social Development, Stanley Katz, et al., 4th ed (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1993), 29.

The English crown responded to Berkeley's ineptitude and Bacon's rebellious acts (whose political antics must wait for a fuller description) with royal commissioners and a royal military presence. Charles II appointed Colonel Herbert Jeffreys, Captain Sir John Berry, and Colonel Francis Moryson to investigate the causes of the rebellion. Berry's naval squadron (with Moryson on board) arrived in Virginia on January 29, 1676/7; Jeffrys, who sailed aboard the royal frigate Rose, arrived on February 11. The autonomous Berkeley resented the intrusion into "his" Virginia by royal representatives. In this, Berkeley proved to be just as obstinate as the Baconians. At every turn he endeavored to thwart Jeffrys investigation, and he persisted in exacting revenge against the Baconians despite a general royal pardon. However, Berkeley was able to continue his revenge only for a short time. In May 1677 he was deposed by Jeffrys and returned to England where died in July before facing the charges that had been leveled against him.117

117Webb, 1676, 163.

Pro-Bacon rebels ascended to power after the after 1676 by joining the royalist resurgence in Virginia. Byrd, who fought with Bacon against the Occaneechee in May 1676, was, after Bacon's death on October 26, still part of those Baconian rebels who actively sought to overthrow Berkeley's government. Byrd had established his headquarters at Tindall's Point (Gloucester). "There Captain William Byrd's Baconian quarters were at the plantation of Colonel Augustine Warner." On January 9, 1676/7, "Bacon's first follower, Captain William Byrd of Henrico, redeemed his rebellion."118 He joined the Berkeleyan Admiral Robert Morris less than three weeks before the royal commissioners arrived in Virginia.

118Ibid., 84, 98.

In the end, the Baconians despised the pre-1676 status quo in Virginia more than they opposed royal oversight. Or differently put, Baconians used the royal officers to undermine William Berkeley and his "Green Spring Faction" and enter the positions of power that Berkeley had denied them. In this sense, Bacon's Rebellion heralded the arrival of a new ruling elite. Jeffrys utilized the now-repentant Baconians, such as Byrd, who cooperated with a resurgent royalism in return for a pardon previously issued, to perpetuate the new royal government of Virginia. In October 1677, Byrd was elected to the House of Burgesses (from Henrico County) for the first time. He replaced the rebel Bacon who had been elected at the outset of the rebellion.

Jeffrys promised "imperial action and internal reform" to the complaints made against Berkeley.119 He accomplished this objective in three ways. First, the crown's officers imposed royal rule in the form of military and political presence. Second, the royal pardon was extended throughout Virginia as a way to eliminate the rebels hesitation in cooperating with the crown. "Finally, by their collection of both county and individual grievances against the old regime and by their systematic cultivation of revolutionary leaders (and of others outside the Berkeleyan clique), the king's men had built political bases for imperial rule both in public opinion and in a new class of rulers, responsive to royal orders."120 Thus, in the aftermath of the rebellion, "royal officials recognized the aspirant newcomers to Virginia, the leaders of the revolution, as part of the province's new ruling class."121

119Marambaud, "A Young Virginia Planter in the 1670s," 141.

120Webb, 1676, 162.

121Ibid., 154.